The herbaria of the 19th century: when botany becomes art and living memory

by Clarisse:)

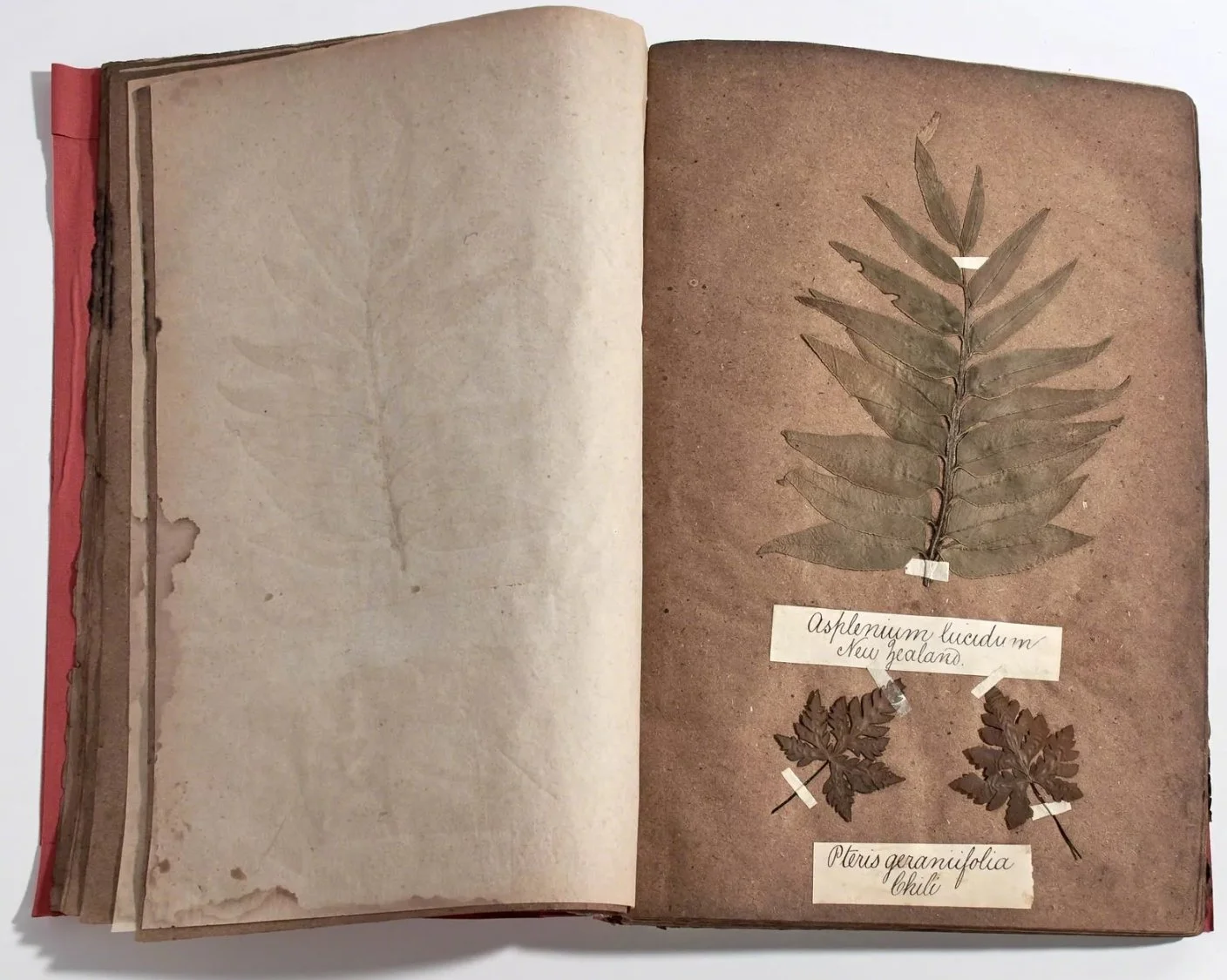

In the 19th century, the passion for plants went beyond gardens. Throughout Europe, a real obsession is established: that of documenting, classifying and preserving the plant world. It is the golden age of herbaria, those collections of dried and hand-fixed plants that hold both scientific knowledge and work of art.

Today, at Dirty Roots Berlin, it is fascinating to see how these careful, patient, respectful gestures of the past are still present in our way of thinking about plants, objects and our relationship with nature.

The herbarium: a science in your hands

The making of a herbarium is first and foremost a matter of science. In the 1800s, botany evolved into a discipline. Carl von Linné, a century earlier, already laid the foundations for modern classification. The great explorations bring in thousands of new plants in Europe. To identify them, study them, transmit them we begin to dry them, paste them, annotate them.

Each specimen is named, dated, located. Botanists, both amateurs and professionals, also become archivists.

The herbarium is both a manual database, a map of the plant world, and a trace of life. Even today, ancient grasslands are used to understand the evolution of ecosystems or climates: where a plant grew, when and under what conditions.

Unlike other sciences of the nineteenth century, botany has the particularity of having been widely accessible to women at a time when university was still forbidden. Women like Anna Atkins, Marianne North and hundreds of anonymous botanists have created their own herbaria, often of exceptional quality.

Anna Atkins is now recognized as the first female photographer. She published in 1843 Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, an illustrated book exclusively of cyanotypes (photos based on marine plants), combining science, art and botanical aesthetics.

It wasn’t just a collection. These women and men took the time to contemplate, to represent the plant, to understand its shape, its function, its discreet beauty. The herbarium became almost a work of introspection.

Herbalism, care and connection to the living

Another essential facet of the herbarium in the 19th century is its medicinal function. At a time when pharmacological knowledge is still very much linked to the plant world, many herbaria include annotations on the therapeutic virtues of plants.

Lime for insomnia, chamomile for digestive ailments, St. John’s Wort for wounds. Herbalism, often passed on by women, especially in the countryside, remains deeply linked to popular culture.

These herbaria are therefore also memories of care, notebooks of use. It was noted the recipes of herbal teas, decoctions, tips to treat winter pains or children’s fevers.

This very empirical approach, deeply linked to experience, finds today an echo in our growing need to reconnect with the living, to natural, holistic forms of care.

At Dirty Roots: gesture, care, contemplation

What strikes at Dirty Roots Berlin is the quality of the gesture. The care given to each plant, each pot, each combination of textures and shapes recalls the same attention that 19th century collectors paid to their herbaria.

It is a place where the plant is respected, highlighted, where the container is designed to marry the plant, accompany it. Here, it is not about stacking pots on shelves: each object is a tribute to the singularity of nature. We find the same slowness, the same precision, the same desire to create a link between humans and plants.

By referring to the old meadows, we are not only looking back. We revisit a way of being in the world: attentive, gentle, manual, respectful. This is exactly what Dirty Roots offers us, at the heart of a world saturated with speed and production.

What if we started picking, observing, noting again?

We are not proposing here to become botanists again. But simply to rediscover this ancient pleasure: that of taking the time to observe a leaf, to smell a scent, to understand a form. To pose, like the herbalists and artists of the nineteenth century, in a posture of wonder. Creating a herbarium today, even symbolically, is recreating the link. It is choosing to slow down, contemplate, and perhaps heal a little.

At Dirty Roots, it starts simply: a plant, a pot, a look.